Summer of Sleaze is 2014’s turbo-charged trash safari where Will Errickson of Too Much Horror Fiction and Grady Hendrix of The Great Stephen King Reread plunge into the bowels of vintage paperback horror fiction, unearthing treasures and trauma in equal measure.

Dennis Etchison (born Stockton CA, 1943) didn’t set out to be a horror writer. While Etchison has been referred to as a writer of “dark fantasy” or of “quiet horror,” in an interview with journalist Stanley Wiater in Dark Dreamers (1990), the author states that he found himself in the horror genre “sort of by accident.” Etchison began writing and publishing science fiction stories in the 1960s, but as the short genre fiction market changed he found his work gained more acceptance in the burgeoning horror fiction field of the 1970s.

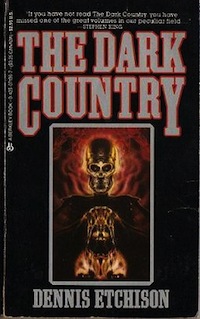

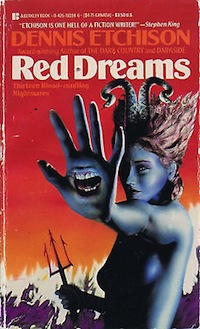

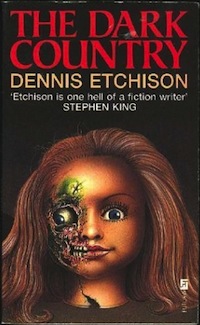

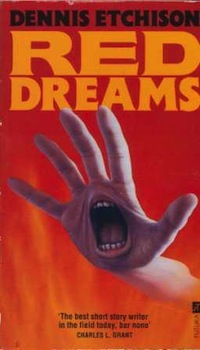

With his bleak, pessimistic, often quite violent tales of people drifting through a modern world of lost highways and all-night convenience stores, mistaken identities and secret sociopaths, how could Etchison have ended up anywhere but the horror shelves? His stories gained plaudits from Stephen King, Ramsey Campbell, Charles L. Grant, and Karl Edward Wagner, and were published in two paperback collections by Berkley Books, 1984’s The Dark Country and 1987’s Red Dreams (both originally put out by specialty horror publisher Scream/Press several years prior).

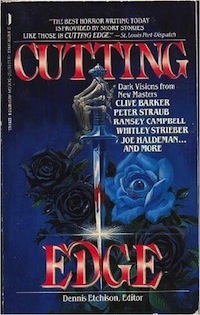

By the end of the 1980s Etchison had become a highly regarded editor as well, gathering brilliant and blisteringly horrific tales of all styles and voices for the anthologies Cutting Edge (1986) and Masters of Darkness (3 vols., 1986–1991). If all that weren’t enough, under his pseudonym Jack Martin (a character with that name appears in many of his tales) he wrote novelizations for films by both John Carpenter and David Cronenberg. Let’s face it: Etchison may not have grown up being a horror writer per se, but he certainly knows his way around the oft-maligned genre. In his introduction to Cutting Edge, he gives a shorthand lesson in the failures of genre fiction during the modern era: Tolkien, Heinlein, and Lovecraft impersonators who refused to engage with the fracturing contemporary world around them. None of that for Etchison.

Like Stephen King, Etchison had many of his short works appear in low-rent 1970s men’s magazines, as well as The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, and various horror anthologies edited by Charles L. Grant, Stuart David Schiff, and Kirby McCauley. These are the stories you’ll find in The Dark Country and Red Dreams. As one might have guessed, his horror stories could also be classified as “soft” science fiction (as he noted to Stanley Wiater) as well as crime/noir fiction. Anyone who’s read widely in these fields will know that those genre lines overlap and blur (think of James Ellroy’s The Black Dahlia, which contains scenes of violence to make any gorehound wince, or George R.R. Martin’s longish short “Sandkings,” which melds SF and horror beautifully); there are echoes of Chandler, Bradbury, and Dick, J.G. Ballard, Harlan Ellison, and “Twilight Zone” scribe Charles Beaumont (under whom Etchison studied in a UCLA workshop in the early 1960s). His paperbacks may have been marketed as modern horror—witness the blurbs and taglines on them, all “blood-curdling” and “master of the macabre” and so on—but Etchison took all those influences and crafted his own particular type of dark, speculative fiction.

What’s truly important, and why Etchison should still be read today, is that his stories are crafted with a true writer’s care; he infuses his work with a literary sensibility, not a pulp one. As someone who loves horror fiction but doesn’t only read horror fiction, I find this quite refreshing. He can be bloody and violent, he can be quiet and intimate, he can be challenging and oblique, but he always uses his own unique template. Etchison’s not afraid to utilize a sort of experimental style to delineate the crumbling psyche of a doomed character. Occasionally his allusive prose and his sleight-of-hand skill at misdirection can mitigate the impact of some stories, so I find a careful approach to him works best. Etchison shows; he does not tell. His work stands out from other ’80s horror because of that; this rule of writing is often the first one jettisoned by horror writers.

A California son, Etchison often sets his fictions in the desert highways and late-night byways of his home state; he knows well this empty land and the darknesses therein. Etchison is very good at writing scenes of shocking violence, but his fiction doesn’t rely on them, as so many horror writers do. There is much psychological violence, distress, dismay, a sense of things being not quite right, of a person not quite at home, wandering lost along a dark highway—and then meeting someone, or something, at the end of the night…

Of his two major collections, I am most partial to The Dark Country. While Red Dreams has its dark gems, the stories in this collection seem darker, meaner, both more graphic and more effectively subtle. “The Late Shift,” one of his most lauded and original works which was first published in Kirby McCauley’s seminal anthology Dark Forces (1980), reveals a sinister source for those poor souls working the graveyard shift in 7-11s and gas stations and diners. Poor souls indeed.

The noir-ish “The Walking Man” put me in mind of the spectacular “modern” noir film Body Heat, which I’m never disappointed to be reminded of. The maddeningly enigmatic “You Can Go Now” finishes without wrapping and bow but I found its dream-like, episodic psychological structure utterly intriguing… even if perhaps it doesn’t quite come together. And then there are the icy merciless horrors of “Calling All Monsters,” “The Dead Line,” and “The Machine Demands a Sacrifice,” which form what Ramsey Campbell calls in his introduction “the transplant trilogy… one of the most chilling achievements in contemporary horror.” Blurring SF and horror in a vaguely Ellisonian manner, Etchison offhandedly imagines a future (?) of living bodies at the service of some (mad) science, evoking specifically Dr. Moreau’s House of Pain. The sentence “This morning I put ground glass in my wife’s eyes,” begins “The Dead Line,” its no-nonsense, amoral tone invoking the hardboiled writers of the 1930s. More please!

“It Only Comes out at Night,” with its generic title, is a traditional horror piece, as is “Today’s Special,” but each is tightly written, offering horror fans the poisonous confections they love. The frigid vengeance of “We Have All Been Here Before” and especially “The Pitch” is quite satisfyingly nasty. Along with his talent for straightforward storytelling, Etchison has a skill for diversion, letting the reader think a story going’s one way when—record scratch—it goes somewhere else entirely. To wit: “Daughter of the Golden West,” which begins as a Bradbury-esque fantasy of three college-age men (the collection is dedicated to Bradbury) and ends with a revelation of one of California’s greatest tragedies. It’s a gruesome delight.

The title story won the 1982 British Fantasy Award and the World Fantasy Award for best short fiction. Nothing SF or noir or supernatural about this piece at all; it reads more like an autobiographical piece of an inadvertently nightmarish vacation. Jack Martin’s friends callously and drunkenly exploit locals at a Mexican beach resort, then he’s forced to face a fate dealt at random. This is not the kind of story you expect to find in a book with the little “horror” label on its spine, but does that even matter? It’s spectacular.

While The Dark Country is where the gruesome edge of Etchison’s blade resides, Red Dreams is its quieter sibling, but no less unsettling or insightful for that. The late great Karl Edward Wagner, in his intro, opines that Etchison’s nightmarish fiction is one made of loneliness, “of an individual adrift in a society beyond his control, beyond his comprehension, in which only sheeplike acceptance and robotlike nonawareness permit survival.”

These are stories for grown-ups, their fears of age and insignficance—like the protagonist of “The Chair,” who attends his 20-year high school reunion and is called again and again by the wrong name, every time different, till one person gets it all too right. The father in “Wet Season” has faced a parent’s worst nightmare but then… it gets worse. “Drop City,” while overlong, is a noir/horror mash-up, slowly—perhaps too slowly—building to an impressionistic finale that seems eerily familiar… if the readers pays close attention.

The thematically ambitious “Not from Around Here” finds Etchison in a quiet Phildickian mode as he slowly introduces us to a near-future and a religious cult whose texts provide perfect insight and pleasure. A lifelong movie fan, Etchison’s future world includes movies never made save in a film geek’s fevered imagination, works like, “Carpenter’s El Diablo, De Palma’s The Grassy Knoll, Cronenberg’s Cities of the Red Night, Spielberg’s Talking in the Dark…”

That’s rich, Etchison having Spielberg make a movie called “Talking in the Dark,” since that’s one of Etchison’s best horror stories! You know how writers hate being asked the utterly banal question “Where do you get your ideas?” (“Poughkeepsie” is Harlan Ellison’s eternal answer)? Here Etchison answers it. Sure, it’s real life; writers are regular people too. Except when they’re not. It’s blackly comic and bloodily conclusive. Another favorite is “White Moon Rising,” a murder-on-coed-campus (shades of King’s “Strawberry Spring”) that fragments character POV as it climaxes.

The fiction of Dennis Etchison insinuates and intimates, brimming with allusions that seem to go right up to the point of comprehension and then dissipate, leaving your imagination tingling, while comprehending his horrors might leave you wishing you hadn’t. Intelligent yet jittery with fearsome anxiety, horrific without clichéd stupidities, the stories found in Red Dreams and especially The Dark Country will reward 21st century horror readers and remind them that the 1980s were a boom for the genre, as it was breaking away from its pulp past and pointing the way to a petrifying—and wholly unavoidable—future.

Will Errickson covers horror from the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s on his blog Too Much Horror Fiction.